Gotta say, this song about Janet Yellen – inspired by “Hamilton” – is seriously badass. I L-O-V-E it.

Category Archives: Economics

1NT: NC Pandemic Unemployment Benefits

During the COVID-19 crisis millions of people became unemployed and Congress responded by passing the CARES Act which, among other things, provided extended federal unemployment insurance (UI) benefits for folks in addition to the UI benefits provided by their states. The two types of federal assistance are pandemic emergency unemployment compensation (PEUC) and pandemic unemployment assistance (PUA). PUA benefits are primarily for the self-employed and independent contractors. Here are some North Carolina numbers from an article in the Winston-Salem Journal:

- $8.16 billion in state and federal UI benefits were paid from late March through Sept. 30

- $670 million were paid from Oct. 1 through December 5, indicating that many people have exhausted their benefits

- 31% of the 4.35 million North Carolinians considered part of the state’s workforce as of mid-October have filed a state or federal unemployment claim, according to DES.

- North Carolinians, at most, could have collected 34½ weeks of state and federal UI benefits, broken down as: 12 weeks of regular state-funded benefits; 13 weeks of federal pandemic emergency unemployment compensation; and between six to 9½ weeks of federal extended benefits.

- Unemployment insurance recipients who qualified for up to 22½ weeks of federal extended UI benefits likely began exhausting them in early November. Most of the rest will be done Dec. 26 unless an extension is passed by Congress during its current lame-duck session.

Today’s 30-Year-Olds Face Steep Challenges

The graph below, which comes from this Axios article, paints a pretty clear picture of the challenges being faced by today’s 30-year-old Americans:

My kids – 25, 24 and 21 respectively – face a different economic reality than their mother and I did at their age in the early ’90s. On average they and their peers are earning the same amount of money as we did, but all of their expenses are higher. The result? Far fewer are getting married, having children or buying a home by the age of 30.

These trends are already having an impact on our country. At my day job I spend my time thinking about housing, the apartment industry in particular, and I can tell you that we’ve been seeing the impact there. That decline in the rate of homeownership you see in the graph above? That translates into more rental housing, which is obviously a positive thing for the apartment industry.

Even when they do get married, this generation isn’t rushing into parenthood mode. From the article:

- Having fewer children: When Boomers were in their 20s, the fertility rate was 2.48, well beyond the replacement level of 2.1. Today, it is just 1.76.

- When a recent survey asked why they were having fewer kids, most young adults said “child care is too expensive.”

And these folks are understandably more risk-averse than we were. After all they saw what happened during the great recession, when millions of people lost their “American Dream” homes to foreclosure. They are much more likely to wait until they know they’re financially solid before they venture into parenthood and homeownership.

So how do we fix this? Well, it begins and ends with household income. Until household income starts increasing at a faster clip than basic household expenses, we’re going to be stuck in place. Sure we can look at trying to control the costs of everyday life, but inflation is an economic reality so even if we reduce the rate of inflation we still need to make up lost ground on the income side. Easier said than done, but it’s something we must get serious about.

Can Poverty Change You Genetically?

This is a fascinating article, written by a former investment manager and current Truman National Security Fellow, who escaped abject poverty in Appalachia, that looks at the early (as of now) research showing the potential link between poverty and genetics. Basically, the stress of poverty might change your body in a way that can be passed to your children and grandchildren.

Even at this stage, then, we can take a few things away from the science. First, that the stresses of being poor have a biological effect that can last a lifetime. Second, that there is evidence suggesting that these effects may be inheritable, whether it is through impact on the fetus, epigenetic effects, cell subtype effects, or something else.

This science challenges us to re-evaluate a cornerstone of American mythology, and of our social policies for the poor: the bootstrap. The story of the self-made, inspirational individual transcending his or her circumstances by sweat and hard work. A pillar of the framework of meritocracy, where rewards are supposedly justly distributed to those who deserve them most.

What kind of a bootstrap or merit-based game can we be left with if poverty cripples the contestants? Especially if it has intergenerational effects? The uglier converse of the bootstrap hypothesis—that those who fail to transcend their circumstances deserve them—makes even less sense in the face of poverty epigenetics. When the firing gun goes off, the poor are well behind the start line. Despite my success, I certainly was…

Why do so few make it out of poverty? I can tell you from experience it is not because some have more merit than others. It is because being poor is a high-risk gamble. The asymmetry of outcomes for the poor is so enormous because it is so expensive to be poor. Imagine losing a job because your phone was cut off, or blowing off an exam because you spent the day in the ER dealing with something that preventative care would have avoided completely. Something as simple as that can spark a spiral of adversity almost impossible to recover from. The reality is that when you’re poor, if you make one mistake, you’re done. Everything becomes a sudden-death gamble.

Now imagine that, on top of that, your brain is wired to multiply the subjective experience of stress by 10. The result is a profound focus on short-term thinking. To those outsiders who, by fortune of birth, have never known the calculus of poverty, the poor seem to make sub-optimal decisions time and time again. But the choices made by the poor are supremely rational choices under the circumstances. Pondering optimal, long-term decisions is a liability when you have 48 hours of food left. Stress takes on a whole new meaning—and try as you might, it’s hard to shake.

As the author points out, this research calls into question the whole concept of poverty as choice, or poverty as the result of laziness, and asks us to reconsider how we address poverty. One thing’s certain: whether or not you agree that poverty has a biological impact, you have to acknowledge that the programs we’ve depended on to fight poverty until now have not worked. Whether it’s because the programs are misguided, or there was a lack of political will to follow through on those programs that exhibited promising results, or some combination of those factors and more, we’ve failed to pull a huge chunk of our population out of poverty and if we want to change that then we’re going to have to make substantial changes. Soon.

Gown Towns Thrive

Yesterday I was in a meeting with several people involved with local real estate development and they were asked what the top business priority is for their county (Guilford, NC) going into 2017. Their response, as has been the case for every year in recent memory, was that job growth will continue to be the most critical issue for their businesses. In the course of answering the question quite a few of these people referenced other cities in North Carolina that seem to be thriving – Raleigh, Cary, Charlotte and “even Wilmington” – were the names I remembered. What stuck out, to me, was that no one mentioned Winston-Salem.

Now let me state up front that I’m not prepared to offer any statistics that compare the jobs situation in Winston-Salem to those in Guilford County’s two cities, Greensboro and High Point. But I will say that if you were to poll most people who pay attention to business in the region, they will tell you that Winston-Salem’s economic recovery from the nuclear annihilation that has befallen this region’s traditional economy is further along than its neighbors to the east. For some reason, though, leaders in Greensboro and High Point seem to ignore what’s going on just 30 miles to their west (and in all fairness the reverse is also true), and as a result no one seems to know why there’s a difference between these two very similar neighbors.

A personal theory is that there are a lot of complex and interwoven factors at play here, but one big one is the presence of Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem. The university, and in particular it’s medical school, has been a partner with the city and local companies as the city moved away from it’s traditional tobacco manufacturing base toward a “knowledge economy” with a niche in the area of medical research. Starting over 20 years ago Winston-Salem’s civic and business leaders recognized the need to re-position the city’s economy and Wake Forest played a significant role in those plans. The results are plain to see in the city’s Innovation Quarter, which is booming and is primed for exponential growth over the next 10-15 years.

30 miles to the east Greensboro actually has more schools, including NC A&T and UNCG, but they don’t seem to have had the same effect on the city’s economy. Yet. We’re starting to see much more activity there, including the Union Square Campus that recently opened and is already bearing economic fruit for the city and there’s PLENTY of potential for even more growth. As long as the city’s leaders continue to keep their eye on the ball there’s a very good chance this will happen, as it has in other college towns.

This article in the Wall Street Journal has a lot of data showing how cities in the US that have strong colleges, especially those with research programs, have recovered from the decline in the manufacturing sector over the last two decades. Here’s an excerpt:

A nationwide study by the Brookings Institution for The Wall Street Journal found 16 geographic areas where overall job growth was strong, even though manufacturing employment fell more sharply in those places from 2000 to 2014 than in the U.S. as a whole…

“Better educated places with colleges tend to be more productive and more able to shift out of declining industries into growing ones,” says Mark Muro, a Brookings urban specialist. “Ultimately, cities survive by continually adapting their economies to new technologies, and colleges are central to that.”…

Universities boost more than just highly educated people, says Enrico Moretti, an economics professor at the University of California at Berkeley. The incomes of high-school dropouts in college towns increase by a bigger percentage than those of college graduates over time because demand rises sharply for restaurant workers, construction crews and other less-skilled jobs, he says.

And here’s the money quote as it relates to local economic development efforts:

Places where academics work closely with local employers and development officials can especially benefit. “Universities produce knowledge, and if they have professors who are into patenting and research, it’s like having a ready base of entrepreneurs in the area,” says Harvard University economist Edward Glaeser.

Let’s hope our local leaders take full advantage of what our colleges have to offer, for all of our benefit.

Winston-Salem as a Case Study

Since moving here in 2004 I’ve found Winston-Salem to be a fascinating study in how to revive a city that had been hit by multiple economic tsunamis in recent decades. It seems that others have taken notice, including a writer who penned a piece for the Christian Science Monitor about how a few US cities can teach the country a little something about democracy (h/t to my Mom for sending me the article). You can find the full article here (second story down), but here’s the segment focused on Camel City:

Winston-Salem, N.C., lost 10,000 jobs in 18 months after R.J. Reynolds moved its headquarters to Atlanta and several other homegrown companies failed in the late 1980s. It was the first of several waves of job losses as the city’s manufacturing base collapsed. Civic leaders chipped in to create a $40 million fund to loan start-up capital to entrepreneurs, hire staff for a local development corporation, and fund signature projects. One of them was the renovation of a 1920s Art Deco office tower into downtown apartments.

This activity helped spur Wake Forest University’s medical school to undertake an ambitious project to create a research park in former R.J. Reynolds manufacturing buildings next to downtown. The school has filled 2 million square feet of empty factories with high-tech companies and world-class biomedical researchers. An adjacent African-American church has turned 15 acres in the area into lofts, senior housing, and businesses. Downtown has attracted $1.6 billion in investment since 2002.

Now people gather to sip coffee, attend concerts, or take yoga classes in a new park in the shadow of the looming chimneys of a former Reynolds power plant. The plant itself is being repurposed into a $40 million hub of restaurants, stores, laboratories, and office space. Students, researchers, and entrepreneurs mingle in the halls and atria of all the former factory buildings, creating the kind of synergetic environment the innovation industry now craves.

Our very own Jeff Smith, of Smitty’s Notes, provides the money quote:

“It wasn’t one person or thing that made it all happen; it was everyone from the grass roots to the corporate leaders coming together,” says Jeffrey Smith, who runs Smitty’s Notes, an influential community news site. “We realized it would take all of us to get this hog out of the ditch.”

Much of the foundation for this renewal had been laid by the time I moved here with my family in 2004, but community leaders have continued to do what’s necessary to keep building upon it. For my job I get to spend a significant amount of time in neighboring Greensboro, a city that is slightly larger but quite comparable to Winston-Salem, and it’s been interesting to see how the two cities have proceeded from their respective economic crises. Winston-Salem has a lot of momentum, and it’s redevelopment seems to be benefiting from consistent collaboration among its community leaders, including elected officials as well as corporate and civic leaders. Greensboro, on the other hand, is making progress but it seems to be in more fits and starts; its progress seems to occur in spite of local leaders’ lack of cooperation and collaboration.

Sure, Winston-Salem has its problems and leaders sometimes disagree on how to proceed, but for the most part its leaders have shown how to lead a community out of the ditch and back on the road. Hopefully we keep it going for decades to come.

Get Used to the Low Home Ownership Rates

This is a cross-post of something I wrote for the work blog:

From the 6/8/15 Wall Street Journal:

The U.S. homeownership rate is below where it stood 20 years ago when President Bill Clinton launched a national campaign to encourage Americans to buy homes. Conventional wisdom says the rate, at 63.7%, is leveling off to where it was for decades before the housing-market peak.

But this is probably wrong, according to research from the Urban Institute, which predicts homeownership will continue to slip for at least 15 years.

Demographics tell the story.

Urban Institute researchers predict that more than 3 in 4 new households this decade, and 7 of 8 in the next, will be formed by minorities. These new households—nearly half of which will be Hispanic—have lower incomes, less wealth and lower homeownership rates than the U.S. average.

The upshot is that fewer than half of new households formed this decade and the next will own homes. By contrast, almost three-quarters of new households in the 1990s became homeowners.

The downtrend would push homeownership below 62% in 2020, and it would hold the rate near 61% in 2030, below the lowest level since records began in 1965.

If You’re a Poor Kid in Forsyth County Then You’re Screwed

According to a recently released report Forsyth County, NC is the second worst county in the United States when it comes to income mobility for poor children. From the report in the New York Times:

Forsyth County is extremely bad for income mobility for children in poor families. It is among the worst counties in the U.S.

Location matters – enormously. If you’re poor and live in the Winston-Salem area, it’s better to be in Davie County than in Yadkin County or Forsyth County. Not only that, the younger you are when you move to Davie, the better you will do on average.

Every year a poor child spends in Davie County adds about $40 to his or her annual household income at age 26, compared with a childhood spent in the average American county. Over the course of a full childhood, which is up to age 20 for the purposes of this analysis, the difference adds up to about $800, or 3 percent, more in average income as a young adult…

It’s among the worst counties in the U.S. in helping poor children up the income ladder. It ranks 2nd out of 2,478 counties, better than almost no county in the nation.

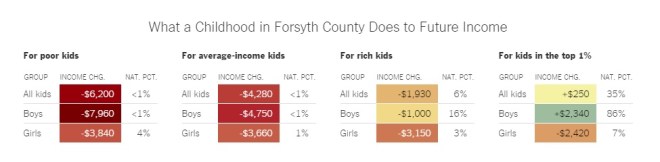

Take a look at this graphic and you can see that there’s a huge disparity between the prospects for poor kids and rich kids in the county:

Forsyth’s neighbor to the east, Guilford County, isn’t much better off:

It’s among the worst counties in the U.S. in helping poor children up the income ladder. It ranks 37th out of 2,478 counties, better than only about 1 percent of counties.

While it would be easy to say, “This should be a wake up call to the leaders of our community” I think that would be a cop out. This is the kind of thing that should concern us all because what do we think will eventually happen if we continue to allow a huge segment of our community to live in circumstances in which they perceive little chance of improving their lot in life? What do we think these young people will do when they lose hope?

So yeah, our elected leaders should view this as an early warning that they need to address these underlying causes of this disparity in opportunity, but this is bigger than them. All of us need to get engaged, through our schools, churches, civic groups, businesses and neighborhoods, in order to begin to make any progress in improving the prospects for our kids’ futures. The underlying issues are systemic – broken family structures, poor educational attainment, too many low wage jobs, etc. – and only a concerted effort by the entire community will be able to address them. If we don’t we will have much larger problems on our hands in years to come.

Winston-Salem and Forsyth County have made a great deal of progress in addressing the major economic challenges that were wrought by the declines of the local manufacturing industries, highlighted by the resurgence of downtown Winston-Salem, but now we need to make sure that the tide rises for everyone, not just those lucky enough to be born into well off families.

From Scarcity Thinking to Abundance Thinking

This Tedx New York talk will really get you thinking about things differently. The speaker presents two radical ideas: first, basic income guarantees for everyone to cover housing/food/health and the second is to allow bots to represent us. You might wonder what they have to do with each other, but the common thread is that we live in a time of technological abundance, not scarcity, and thanks to the coming wave of automation and the continuing impact this technology is having on our workforce we have to invert our thinking about public policy in response. Whether you agree or disagree I think the 17 minutes you spend with this will cause you think about how we think about things in our society:

Before you jump to any conclusions, one of which is most likely “Why in the hell should be pay people even if they aren’t working” you should stop and really think through what he’s saying and the opportunities that these ideas present. Once you allow yourself to move beyond the knee-jerk reaction of “I don’t want lazy lowlifes benefitting off my hard work” to really thinking this through I think that you’ll find that the premise leads to some interesting potential outcomes.

A Tale of Two Forsyth Counties

If you set up a Google news alert with the keywords “forsyth county” you’ll get a lot of news about two different places – Forsyth County, NC (where I live) and Forsyth County, GA. Today I saw a story about each from their local news outlets with the following headlines:

- Forsyth County Remains Healthiest in Georgia (GA)

- Forsyth County Slips Again in Health Rankings (NC)

If you read the articles you’ll see that Forsyth County, GA ranks first in its state and Forsyth County, NC ranks 29th in its state. So is my home county significantly less healthy than its counterpart in Georgia? If you look at a comparison of the two (see table below) using data from the countyhealthrankings.org you can see that Georgia has better numbers in many categories, but they really aren’t that far apart when you take into account the population size of each county. According to the US Census North Carolina’s Forsyth had 360,221 in 2013 and Georgia’s had 195,405 so even if you looked at some raw numbers that look pretty bad for NC, the population difference changes things. For instance:

Premature Deaths: NC 7,218 vs GA 4,234 but if you adjust for population size you see that NC’s is 2% of its population and GA’s is 2.16%. Still a decent difference but not as stark.

Then there’s this number:

Sexually Transmitted Infections: NC 755 vs GA 91

No amount of adjusting for population makes that better for NC (and gross!), and as you can see we in Forsyth of NC fare worse than GA based on our behaviors in general. Luckily we’ve got an awesome doctor/resident ratio to help deal with the consequences of our sins:

Ratio of primary care physicians to population: NC 945:1 vs GA 2,506:1

Ratio of dentists to population: NC 1,657:1 vs GA 2,677:1

Ration of mental health providers to population: NC 406:1 vs GA 2,246:1

Probably the biggest difference between the two counties, and a huge contributor to the health differences, is that Forsyth, GA appears to be far more affluent than Forsyth, NC. In addition to the numbers in the chart below (NC’s child poverty rate 3x greater, single parent homes 2.5x greater violent crime 2x greater per capita) you have this data from the US Census: median household income (2009-13) in Forsyth, GA is $86,569 and in NC it’s $45,274.

Money may not buy love, but it sure does help on the health front.